Of all the Academy’s activities, our terminology work – specifically, the coining of Hebrew terms – may well rank as the most salient in the public imagination. Our efforts continue the work begun by our predecessor, the Language Committee, over a century ago. The Language Committee began coining and disseminating Hebrew words and terms during the revival of spoken Hebrew, when the language still lacked many basic words needed for everyday communication, such as “tomato.” Although Hebrew has been a fully functional modern language for decades now, the Academy continues to receive requests for Hebrew terms, both for common speech and for professional discourse, typically from speakers seeking Hebrew terms in lieu of prevalent foreign ones.

The Academy’s Approach to Terminological Innovation

To Coin, or Not to Coin?

We are often asked why the Academy has not coined Hebrew alternatives for words such as technologia (‘technology’), televizia (‘television’), autobus (‘bus’), and, of course, academia (‘academy’). The Academy’s dictionaries of professional terms actually contain many borrowed foreign words, such as electronica (‘electronics’), meteorologia (‘meteorology’), and psychologia (‘psychology’). Despite the expectation or demand from some quarters that the Academy provide a Hebrew equivalent for every foreign term, in certain cases we in fact choose not to pursue one.

While those who lobby for a Hebrew alternative to every foreign term may act from a deep love of the language or regard for stature and independence, the embrace of loanwords does not necessarily reflect disrespect to Hebrew or indifference to its welfare; in fact, some would contend that loanwords enrich Hebrew by connecting it to other languages and cultures. In any case, texts from across the ages reveal that for millennia Hebrew has borrowed words from other languages. To cite just a few examples: in Biblical Hebrew we find the words אִכָּר (‘farmer’) and הֵיכָל (‘palace’) of Akkadian origin and the word דָּת (‘law’; in contemporary Hebrew, ‘religion’) of Persian provenance; in Rabbinic Hebrew, borrowings from Greek, Latin, and Aramaic include פַּרְצוּף (‘face’), Sanhedrin (‘council of leaders’), sandal (‘sandal’), kirkas (‘circus’), and אִילָן (‘tree’); and Medieval Hebrew contains many words adapted from Arabic, such as מֶרְכָּז (‘center’) and אֹפֶק (‘horizon’). The Academy takes a middle path with regard to loanwords, considering each term individually and deciding whether to adopt a Hebrew equivalent to it.

Whether the Academy ultimately chooses to keep a borrowed foreign term or to replace it with a Hebrew one depends on many factors, such as: how deeply entrenched the foreign term is in contemporary Hebrew; how easily Hebrew speakers can pronounce it; whether it has spawned derivative words in Hebrew, like the verb טִלְפֵּן (tilpen, ‘to telephone’) from the borrowed noun טֵלֵפוֹן (‘telephone’); whether it holds cultural value (e.g., the name of a traditional ethnic dish); and whether a catchy and appropriate Hebrew equivalent has been proposed.

How We Coin Hebrew Terms

If the committee members discussing the term decide that it warrants a Hebrew equivalent, they try to find a solution within the existing Hebrew lexicon, whether by constructing a distinctive phrase (e.g., חַדְשׁוֹת כָּזָב for “fake news”), choosing a single word already in use in a related sense, or “recycling” a word that has fallen out of use, sometimes changing its meaning slightly. For instance, the Hebrew term for an open-air museum, מוּזֵאוֹן קָטוּר, taps the Biblical adjective קָטוּר to express “open-air”; in the one appearance of the word in the Bible (Ezek. 46:22), it modifies the noun חָצֵר (‘court’) and may mean ‘enclosed.’

If the committee members resort to coining a new Hebrew word, they typically derive it from an existing root (shoresh), feeding the root into an appropriate word-pattern (mishkal). For example, the neologism הֶדְבֵּק (hedbek), approved in 1997 for “collage,” is derived from the root דב"ק, d-b-k. The word-pattern of הֶדְבֵּק identifies it clearly as a noun; and since Hebrew speakers are already familiar with the verb הִדְבִּיק (hidbik, ‘to glue’) that shares the same root, they can surmise upon encountering הֶדְבֵּק that its meaning bears a connection to gluing. Similarly, the word נִזּוּם (nizzum), approved in 2016 for “piercing,” announces itself as a verbal noun by means of its word-pattern; and speakers can easily recognize it as a relative of the word נֶזֶם (nezem, which in classical Hebrew texts denotes a nose ring or an earring and today may also refer to a nose stud), since both words share the root נז"ם, n-z-m.

The Road to Approval

New Hebrew terms make their way to the Academy plenum for approval either along the track for professional terms, which handles the vast majority of the terms, or along the track for words in general use. Naturally, words in general use tend to garner more attention from the public.

Most of the professional Hebrew terms that the Academy approves come before the plenum as English–Hebrew lists or dictionaries of professional terms in a given field, after having been prepared by a dedicated committee formed for the purpose; occasionally the Hebrew professional vocabulary in a given field is already established, and the dictionary serves to formalize it and to provide English-language equivalents. Generally the committees consist of several professionals in the relevant field, who contribute their expertise about the subject matter, and one or more representatives of the Academy; some committees arise at the Academy’s initiative, others – at the initiative of the professionals. Most committees work for at least a few years; some work for decades, producing multiple lists on different topics within the field. After preparing a list, disseminating it for comment, discussing the comments, and making revisions, the committee presents the list to the Central Terminology Committee, one of the Academy’s standing committees, for review. The Central Terminology Committee may reject some Hebrew terms, suggest changes to them, or send them back for further discussion. Once the entire list gains the approval of the Central Terminology Committee, it proceeds to the plenum for approval.

Occasionally the Academy receives a request to establish a Hebrew equivalent for a specific professional term that does not fall under the purview of an active committee; in such cases the Academic Secretariat may recruit an ad hoc committee of professionals to discuss the term. From there the term proceeds to the Central Terminology Committee, and then the plenum, for approval.

In the other terminology track, the Committee for Words in General Use considers words and terms commonly used by the general public, such as “collage,” “piercing,” and “fake news.” Here the initiative tends to come from members of the public, who contact the Academy seeking a Hebrew alternative to a foreign term commonly used in everyday speech; often they suggest a specific Hebrew equivalent. Whereas a list of professional terms may leave some foreign terms unchanged, simply transcribing them into Hebrew, the Committee for Words in General Use brings only Hebrew proposals to the plenum. The Committee must therefore decide in each case whether coining a Hebrew equivalent is warranted and consider whether it has a worthy proposal.

Public Reception of the Academy’s New Hebrew Words

A new Hebrew word that enters the language through this very deliberate process faces an uncertain fate, raising an intriguing question: is it possible to predict whether a new coinage will catch on and become widely used? Some factors that may affect the outcome include the ease with which speakers perceive the root of the word and grasp its meaning; the level of entrenchment of the foreign word being replaced; and the brevity and simplicity of the Hebrew term. Mass-media exposure may contribute decisively to the quick absorption of a word; professionals can also raise a word’s chances by including it in their lexicons. The experience of the last 100+ years of coining new Hebrew terms shows that occasionally a decade or more may elapse before a word takes off and gains wide usage. For example, the now-commonplace word מֵידָע (‘information’) was coined in 1959 as a psychological term and entered more general usage only in the 1990s.

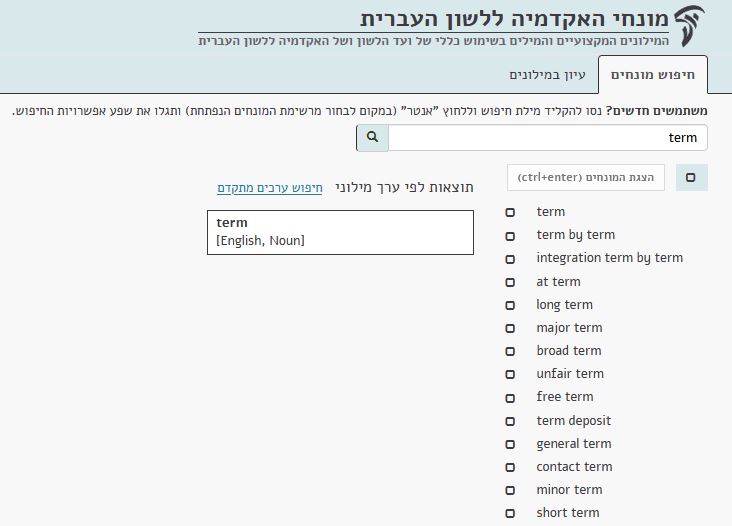

The Database of Hebrew Terms

The Hebrew terms approved by the Academy and by our predecessor, the Language Committee, are accessible to the public online in a searchable database on our terminology website. The site also enables users to browse individual dictionaries and includes scans of the dictionaries published in print. Note that while most of the Academy’s dictionaries are English–Hebrew, some of the Language Committee’s dictionaries do not provide English terms opposite the Hebrew ones (usually they provide a foreign equivalent, but it may be in German, French, or another European language).